What drives veterans to suicide?

There is no doubt one question left unanswered as we witness the daily advances made by the Taliban in Afghanistan: what difference did an American presence make? The same extremist group the U.S. sought to topple after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, remains strong, bent but unbroken. On Sunday, Talib fighters seized three Afghan cities, including the commercial hub of Kunduz.

Over the last week I’ve been steeped in two books, one about Afghanistan, and one about the experience of war. Both were written by Sebastian Junger, who appeared briefly in a newsletter from last week. When he and I last spoke, we discussed how the camaraderie and self-sacrifice, the survival training and heightened awareness, follows soldiers back home. It is there that it is of little use, but such responses do not have to be seen as alien.

That which the soldier carries home is a valuable tool that could be used to improve society. But first the society must collectively understand and address the moral injury garnered through combat duty.

Matthew Hoh is a member of the advisory boards of Expose Facts, Veterans For Peace and World Beyond War. In 2009, he resigned his position with the State Department in Afghanistan in protest of the escalation of the Afghan War by the Obama Administration. He previously had been in Iraq with a State Department team and with the U.S. Marines. He is a Senior Fellow with the Center for International Policy.

Among other honors and distinctions, he was named the Ridenhour Prize Recipient for Truth Telling in 2015 and last year was awarded as a Defender of Liberty by the Committee for the Republic. (After Junger’s book, Tribe, was published, Hoh reviewed the book for Foreign Policy. In his review he wrote that Junger had done a disservice to veterans by misinforming the public about trauma and the relation between PTSD, combat, and suicide.)

We spoke last month.

Your illuminating piece on the history behind reckoning (publicly) with the high suicide rates among veterans raised an interesting point: guilt is what drives a veteran to suicide. You wrote that it's something with which all service members can relate. For readers who aren't veterans, can you explain that connection between trauma/warfare and guilt?

What differentiates the trauma war veterans go through, compared to civilians and veterans who have not been to war, is that combat veterans are perpetrators. Trauma is not rare in our society and our lives. About 60% of men and 50% of women have experienced a traumatic event, while studies regarding adverse childhood experiences show that close to 50% of children in the US experience a traumatic event before adulthood.

What many war veterans go through is that they are often perpetrators rather than recipients of trauma. Combat veterans many times are the ones who are carrying out the acts that later lead to mental, emotional, and spiritual distress. These acts may violate the veteran's moral, ethical, and religious codes, thereby violating or transgressing who the veteran thought they were. This type of trauma is known as moral injury.

Moral injury also entails not acting. So, a person can suffer moral injury because they fail to do something, especially if it is something they believed they would have done based upon their values and principles, e.g., a soldier hesitates to pull their trigger and a friend is killed by enemy fire.

A third aspect of moral injury involves betrayal by an institution, respected leadership, or a higher power. With this, again, through action or inaction, you have betrayal by someone or something that is trusted. So you are sent to war, and you are told the purpose of the war is to protect your country from a terrorist attack. You and others sacrifice because you believe what you are doing is just and necessary, but then you learn it was not true. That sort of further betrayal impacts the moral injury a veteran may be feeling as it aggravates mental, emotional, and spiritual distress, as detailed above. A young man or woman goes to war, they do things that transgress their own moral beliefs and values, and they cannot justify those actions as part of a larger mission or purpose.

This form of moral injury is seen in victims of military sexual trauma (MST). Many victims of MST, both male and female, are assaulted and raped by leaders in their chain of command. They then find those who attacked/raped them protected by senior members of their chain of command. You can thus see how moral injury can be compounded on multiple levels, both through personal and institutional action and inaction.

Many are keen to separate moral injury from PTSD. I believe that to be correct. These feelings of guilt, shame, and regret, as well as the experience of betrayal, shake the very foundations of who we are. Shake is not strong enough of a word. Moral injury destroys the very foundations of who we are. Many people are familiar with how extreme and distressing feelings of guilt can be when we have betrayed a family member, partner, friend, etc. People can recall these experiences and remember how devastating and distressing that guilt, shame and regret were. This brings us to the second key difference between combat veterans and those who do not have those experiences.

Most war veterans cannot repair or atone for the damage that they believe they have done. It is extremely difficult for a veteran to return to Iraq or Afghanistan, ask for forgiveness, make amends, repent, etc. In our relationships in civilian life, when we must deal with the guilt of our actions, we often have the opportunity to ask for forgiveness, admit what we did, correct our mistakes, repair the relationship, etc. For war veterans, however, that is exceedingly hard to do, if not impossible.

This shame and frustration compound further by our society's glorification of war and veterans, which, in turn, causes further distress to veterans. Imagine you feel guilty for what you did in the wars; the guilt is distressful; it ruins your life (relationships, work, education, community, sex, finances, substance abuse, etc.) and leads to thoughts of suicide. Then you attend a baseball game and are asked to stand up to be applauded for what you did in the wars. You are experiencing severe trauma from the actions you did/did not take, struggling with debilitating feelings of betrayal, are unable to ask for forgiveness or repent, and then you are applauded and told you are a hero.

This lack of understanding by family, friends, neighbors, co-workers, strangers, etc., causes these feelings of guilt, shame, regret, and betrayal to be further aggravated.

How does a withdrawal without victory, as in Afghanistan, impact that sense of guilt vis-à-vis honor and service?

I think some veterans are bothered and upset to the point of having mental health concerns by the betrayal they have felt in these last wars. There have been nearly 3 million of us who have taken part in the wars. So, of course, there is a broad spectrum of feelings and emotions. However, it is important to note that service members and veterans have favored ending the wars or have said the wars have not been worth fighting for more than 15 years. Polls and studies have shown soldiers and veterans have been in favor of ending the wars, with majorities of veterans now saying these wars were not worth fighting.

Some have taken part in these wars who will fall in with the characterization of a loss of honor, but I don't know of any. I think this concept of dishonor comes primarily from politicians, pundits, generals, and others who want to romanticize the wars and continue them. The veterans I know who took part in combat, by and large, found honor in how they conducted themselves and took care of one another. As stated, most of them did not believe in the purposes of the wars and thought the wars were not worth fighting. There is a great deal of anger and frustration over the wars and how they were unsuccessful. Still, I don't believe that ties into a concept of honor as much as it does with feelings of being betrayed and having taken part in unjustifiable or purposeless wars.

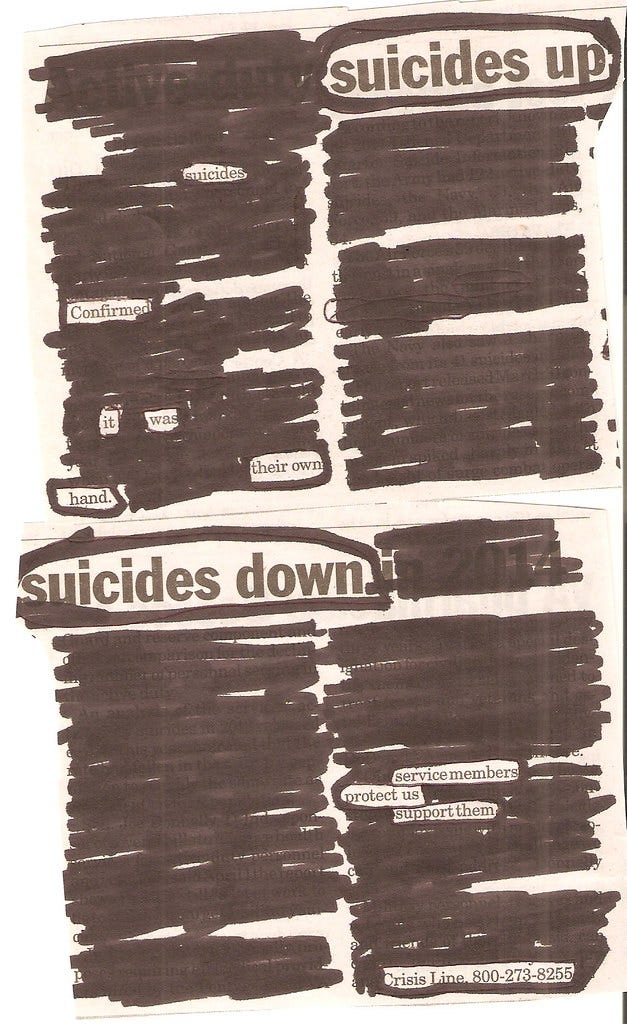

Reporting on veteran suicide rates until recently was impacted by politics. Now that there's more transparency, how in your opinion have the moral narratives of America's wars been impacted?

There needs to be much greater transparency with veteran suicides. It was only in 2014 the VA released data on veteran suicide rates for those who had deployed. Since then, information has been narrower in focus and description. It would be helpful to know which veterans had deployed and which veterans had taken part in combat. This information can be gathered by the Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs. Yes, it would be time-consuming and complex, but it would be worthwhile. However, I fear that it is politically problematic for the US government to admit that its war veterans are killed by suicide because of moral injury sustained in the wars.

The moral narratives of the war don't seem to hold up with any inspection. The governments the United States has created and sustained in Iraq and Afghanistan are corrupt, systematically violate human rights, are misogynist, and have been fraudulently elected. Claims about progress, both in Iraq and Afghanistan, just are not true. 80-90% of those buildings, schools, health care centers, etc. that were supposedly constructed by the US either were never built or can't be found. The claims that millions of Afghan girls went to school have been exposed as lies and "baloney" is the word used by the US Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction on claims that life expectancy went up in Afghanistan. This is not my opinion but what Afghans say, what government officials have found, and what those who led the war admitted.

I think many veterans who fought in Afghanistan hear how the United States did great things for Afghanistan. Maybe that is true for some parts of Kabul and some parts of other northern cities, but where the US soldiers were in the south and east of the country, life has been miserable, brutal, and dangerous for the people there. So, I think many of us recognize there was no benefit to our presence, particularly as a victory by the Taliban was inevitable. As one soldier said to me in Nangahar province in 2009: we should start shooting the 12-year-olds. That bitter tongue-in-cheek comment was truthful because that staff sergeant knew that the Taliban were fighting us because we were occupying them and that the war would continue as long as we were there.

At the end of your piece you note the cost of war led you to struggle with suicidal tendencies, a product of war and the moral injury therein. What pulled you through?

The only reason I am still alive is that people helped me. I had a significant other who forced me to get help, and I got into the VA system because of her efforts. Via the VA, I received treatment and therapy that was not just life-saving but life-changing. It is impossible, I think, to get through all of this (moral injury, PTSD, TBI, and secondary depression and substance abuse) without professional help. Perhaps it is better to say it is nearly impossible, as some people may be able to do it independently. There are hundreds of thousands of us going through it (VA figures show 10-20% rates of PTSD and TBI for veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan), and there will always be exceptions to the rule. For most of us, though, we need professional help. We also need to accept that managing these problems and healing will most likely be a lifetime process. Most of us are men and women who are high functioning, put others first, don't want to be seen as weak, etc., so accepting help, let alone a lifetime of it, is a troubling and complicated process.

This is why I am so concerned that veterans understand what is occurring to them and that they are not alone in their struggle. Friends and family member suicides do not need to be surprising, unexplainable, or inevitable. Veterans, family members, and friends should know that help is available and that help works.

Finally, it is essential to note that if moral injury is a consequence of action, inaction, and betrayal, and since none of us have time machines to go back and change things, then the antidote is to act justly and morally in our present lives. Live a life following our values, be honest with ourselves intellectually and morally, and live lives of purpose and meaning. I do not know what else we can do after being at war.

The Department of Veterans Affairs maintains a hotline for veterans in crisis that operates 24 hours a day. Call 1-800-273-8255 and press 1, go to veteranscrisisline.net/chat, or send a text to 838255.