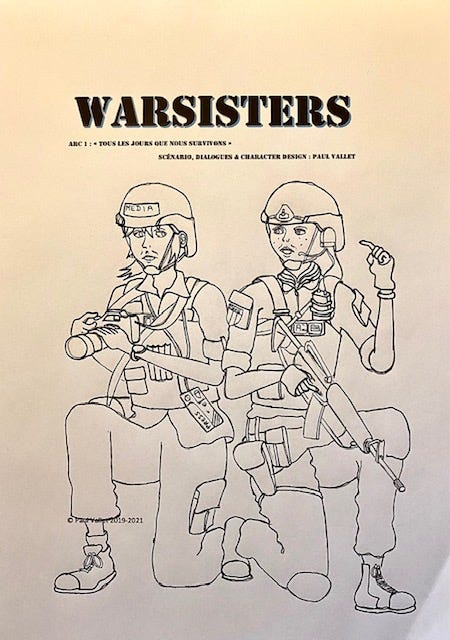

At war with 'Warsisters'

A fictional story based loosely within the theaters of conflict in Syria and Iraq, Dr. Paul Vallet’s upcoming graphic-novel, Warsisters, explores counterinsurgency through the lens of two women, Joëlle and Raphaëlle, a soldier and journalist, affected by these wars.

Dr. Paul Vallet is a dual U.S.-French citizen and academic, who teaches Modern History and International Relations. He was educated at Sciences Po in Paris, the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, and received his PhD in History from Cambridge University.

He also served with the French Army’s 110th Infantry, Franco-German Brigade, for his compulsory military service.

He now resides in Geneva, Switzerland, where he is an Associate Fellow at the Geneva Center for Security Policy. I spoke to Dr. Vallet about how the “forever wars” influenced his work. We exchanged questions over email. This interview has been edited and condensed.

You've been working on this project, on-and-off, through the rise and ongoing withdrawal of US and NATO forces across the Middle East. How has the course of regional conflicts impacted your approach and style?

I’ve been able, both in a professional and private capacity, to follow the course of these conflicts through my entire adult life. I would say I am trying to bring a long view perspective to the story I am telling. In writing a slightly fictionalized account set in the present and near future, I’m also looking for a way to impart lessons we can gather from this long view.

Your inspiration derives from this unfortunate idea of the “forever war.” Tell me about that.

I chose to frame the story as a continuation of the coalition’s engagement against jihadist fighters in Iraq. My main inspiration for the story has been the US and NATO intervention in Afghanistan since 2001, the intervention in Iraq in 2003 through 2011, and by extension the conflict in Syria, and French-led intervention in Mali and the wider Sahel in 2013. What’s especially striking is that, in each case, after an initial, fast-paced, and evolving initial phase in which success was usually measurable, all of them turned into a “forever war.”

Our societies are capable of expelling an excessive amount of resources — from money to military personnel — to keep fighting, despite our core objective of defeating jihadism, politically and militarily, and stabilizing the region eluding us. There is also a sizable disconnect between the battlefield and the home countries of the soldiers sent abroad to fight.

I want to project a compassionate look at the participants of this war, from combatants to civilian casualties, and reporters and aid workers in war zones, alongside their loved ones back home. I reflect on the disillusion in all of them, as well as, how everyone tries to do the best they can in situations they have no control over. I also consider how technology and instant communication doesn’t erase the most primitive aspects of human warfare.

As when working on a non-fiction historical or political account, I’ve documented my work through academic, military and journalistic sources, sticking as closely as possible to real strategic and tactical situations, developments and outcomes.

And this project also reflects your own time in uniform?

My godfather, a veteran of the Korean war and a war correspondent in Vietnam, once saw a picture of my platoon resting in a field in Germany during an exercise and commented, “Soldiers just look the same across the ages.”

I can't compare my experience as a conscript in Central Europe in 1994 - 1995, with what service members experienced in the Middle East and Africa today. But there are some common aspects of military life: communal living, varied disciplinary regimes, issues with equipment, bland food, tiredness, attempts at escapism, and, having experienced it from the enlisted ranks, a certain amount of powerlessness.

I also recall the solidarity that emerges among teams, the camaraderie, the officers we looked up to, and the petty feuds or officers we weren’t impressed with.

How do you feel these impressions of war have changed?

My generation was the last to experience compulsory military service in France and in Europe, a practice that ended in the United States and United Kingdom over two decades before. Our experiences were different from those of the all-volunteer armies of today. They were informed by the Cold War, and set in Europe, a far cry from today’s information-age and asymmetric conflict in Africa and the Middle East.

I feel as others who have no experience of conflict or connection with the military don’t consider conflict in the same way as someone with experience in the military.

I find the disconnect between the military and civilian universes troubling. As citizens, we are called to make political decisions, including those regarding war and peace. Those of us that don’t have the personal experience of the military and its missions, also need reliable reporting and testimonies to enlighten them, especially in order to understand what happens to those who are sent to fight wars on their behalf.

I believe this can be done through well-done works of fiction. That’s how I want to use the experience of my time in uniform, such as it was, to inform my art and make it as educational as it can be for readers.

The protagonists are two young French women, reflecting, as you once noted, "the phenomenon of massive female presence in the armed forces." What prompted this choice?

I originally thought about writing a story about women at war after Desert Shield-Desert Storm. There were many roles that had been filled by women in the professionalized U.S. armed forces.

This was completely different from the situation I witnessed a couple years ago when I served in the French army. The disconnect between the civilian world and the professional military also raises questions about the role that women play in warfare today, and also in reporting about today’s warfare.

My idea was to set this encounter between two women in a war zone: Joëlle, a soldier, and Raphaëlle, a photojournalist. They are close in age, and have some similarities in their social backgrounds, but their education and their professional callings are quite different. Yet, the common experience of the war zone eventually brings them closer together and they become Warsisters.

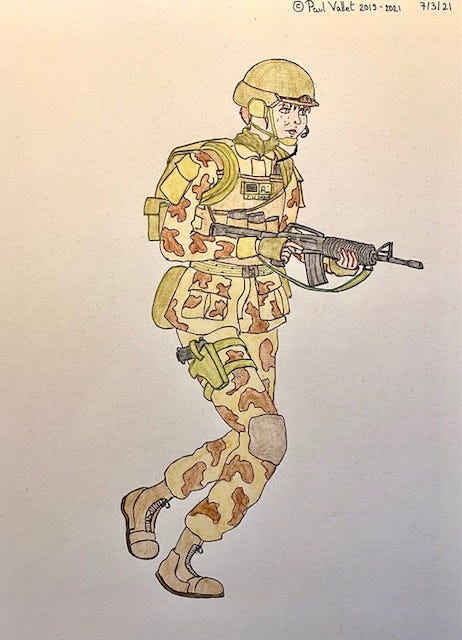

I believe this is a story of women at war worth telling. When I served there were only nine women in my regiment. Today many more ranks are open to women including most combat positions on land, sea, and in the air. This is a newer phenomenon in the French forces than it is in the U.S., hence the interest in setting this story in the context of a French engagement in coalition operations in the Middle East.

My protagonists are both affected by the war — one fighting it and the other reporting it to the public at home. Both will suffer from trauma after they’ve returned and will have to help each other recover from it. I wanted to offer a rather optimistic outcome for both characters, even as the war that brought them together rages on. If it has a single redeeming quality — like any other natural or man-made disaster— war forges bonds between people trying to overcome it, through caring for each other despite the heartbreaking challenges and sorrows that war creates.

I wanted to tell the story with a sympathetic and non-judgemental angle towards my characters, even their flawed behavior. I’ve taken the same attitude towards my depiction of the war. The well-meaning intent of the first intervention goes hand in hand with the contradictions, the cruel and indecisive outcomes which make you question “what was it all for?”

War is hell. We need reminding of it these days when it’s more easily associated with video games by the public and armchair strategists.

What you’ve just read is 100% independent journalism. It’s a product of your generous contributions and support.

War, U.S.A. doesn’t exist without you. And the stories we uncover and share could not be told without our paid subscribers.

We welcome our free list subscribers (and those who share our stories on social) — but if you can afford the cost of this thrice-weekly newsletter ($5/month or $45/year), consider becoming a paid subscriber today.

Why Subscribe?

Paying subscribers get access to exclusive articles, interviews, and drafts of longer projects — they also get to participate in weekly discussion threads, comment on articles and posts, and receive a roundup of the week’s most important U.S. Military and Veterans news.

Email me at kenneth.r.rosen@gmail.com

Already a subscriber? Give War, U.S.A. as a gift.

Or, if you liked this post from War, U.S.A., why not share it?